Reflections on Jung, Archetypes, and Men’s Mental Health

When I began my training in Jungian analytical psychology, one question kept coming back to me: How do Jung’s ideas connect with the reality of everyday clinical work? One of the first points of connection I found was the archetype of the Puer Aeternus — the “eternal child.”

What is the Eternal Child?

The eternal child carries a double meaning. On the one hand, it represents playfulness, creativity, and the spark of imagination. On the other, it can show up as immaturity, fantasy, and avoidance of responsibility. In practice, we may see men who are charming and full of ideas, but who struggle to ground themselves in relationships, work, or everyday life.

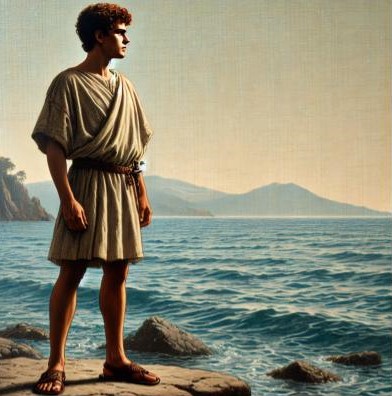

Literature is full of examples of this figure: The Little Prince, Goethe’s Werther, Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, and of course Peter Pan. These stories resonate because they capture something we all recognize — the part of us that resists growing up, and the longing to stay in a safe, magical world.

Why It Matters for Men’s Mental Health

Working in psychiatry and public health, I’ve seen how strongly this archetype connects with the challenges many men face. Men are less likely to seek help, less likely to take antidepressants, and more likely to engage in risk-taking, substance use, or even suicide. They often carry silent struggles, shaped both by their personal histories and by cultural expectations of masculinity.

The mother–son dynamic, for example, can deeply influence how the eternal child archetype is lived out. If the mother is experienced as overprotective, idealized, or even overwhelming, the son may find himself trapped in fantasies rather than able to live out his own grounded path.

From Shadow to Potential

But the eternal child isn’t only a burden — it also carries hope. Like the image of the child at Christmas, it can symbolize new beginnings, creativity, and renewal. When men learn to recognize this archetype in themselves, they can shift from being stuck in endless fantasies to using that childlike energy for growth and creativity.

Therapy can help with this transition. Instead of being pulled backward by a regressive, infantile child, the man can imagine the child walking ahead of him — leading toward something new, playful, and alive.

A Wider Conversation

I believe that exploring archetypes is not about putting people in boxes, but about offering new ways of seeing. My hope is to bring these reflections into broader discussions about men’s mental health, where stigma still prevents many from speaking openly.

Perhaps the real task is to create spaces — in therapy, in families, and in communities — where men can integrate both their strength and their vulnerability, their adult responsibility and their eternal child.